I started teaching English full time in a comprehensive vocational/technical high school in 1971. My first students were a difficult lot. While many of them were skilled in their chosen trade study, their reading and writing skills were not at all good.

Back then, many schools in the county sent their poor academic achieving and behavioral problem students to the vocational schools to "get rid of the problems." Teaching students who had been rejected like that was always a challenge. The upside was how rewarding it was when I was able to help students succeed and discovered a lesson in English class that really grabbed their attention and encouraged them to learn.

Back then, all we really worried about was helping students get ready to go out and earn a living on the job. English class was filled with lessons on practical writing/reading skills. Students learned about handling bank accounts, filling out income tax forms, writing basic resumes, filling out job applications, writing business letters of various kinds, and learning how to read and deal with any other kind of paperwork they might encounter in the real world of work.

As practical and useful as it all was, these classes were not exactly the most inspirational experiences. Mentally challenging? Not at all. Stimulating? Not often. I mean, just how many stories can you read about how Johnny went to work to earn enough money to buy a used car?

Somewhere along the line, I, still able to develop my own curriculum instead of being dictated to by a set and formal list of absolutely required material, decided to try something different.

Since I loved Shakespeare, I decided to teach my class Hamlet. I have always loved the play, and hoped some of my enthusiasm might rub off on my class of 11th grade welders who were totally turned off by English class.

I can still remember sitting across from my principal when we discussed my lesson plans that week. He looked over his glasses at me and said, "You can't teach Shakespeare to welders."

"Of course I can," I replied and despite his skepticism, he signed off on the plans and shaking his head sent me off to what he was sure was going to be slaughter.

"Of course I can," I replied and despite his skepticism, he signed off on the plans and shaking his head sent me off to what he was sure was going to be slaughter.I won't say it was easy, but ultimately, the experiment was a dramatic success. The story of Hamlet is so powerful and the repeated crises of conscience Hamlet experiences throughout the play really caught the class's attention. These students had never experienced great literature. They'd spent so much time filling out job application forms they'd missed out on the better lessons of the English language.

In the following years, students in my classes read and studied Shakespeare, challenged each other to soliloquy contests, walked through the halls of the school quoting the Bard, and in one year, establishing their own little fan club to go to New York to attend the opera. (That after introducing them to the legend of Siegfried and the Ring of the Nibelung)

All was going well. Then, in the later 70's along came the State of New Jersey and a new initiative to "make education better." This was the beginning of T & E: Thorough and Efficient. The idea was to make sure every student in NJ schools was getting a T & E education.

As well intended as that might be, like all such programs, the politicians and educational experts who invented the plan needed some way to evaluate it.

The answer? Why, tests, of course.

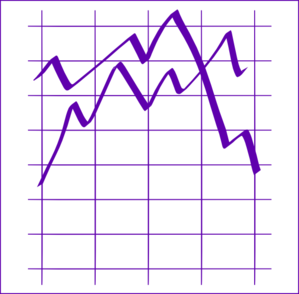

It began with internal classroom control, in the hands of the teachers. I my school, I was given a pile of graph charts, one of each student. (At that time I had perhaps 150 students a day to teach.) I was expected to give them a pre-test at the beginning of the school year, and a post-test at the end of the school year. I was the one writing the tests specific to my class, knowing what I planned to teach during the year. The idea was that students would not score well on the pre-test since it measured the skills I expected to teach, and then at the end of the year, their scores would rise, proving I had been successful in teaching them all the skills and material.

It began with internal classroom control, in the hands of the teachers. I my school, I was given a pile of graph charts, one of each student. (At that time I had perhaps 150 students a day to teach.) I was expected to give them a pre-test at the beginning of the school year, and a post-test at the end of the school year. I was the one writing the tests specific to my class, knowing what I planned to teach during the year. The idea was that students would not score well on the pre-test since it measured the skills I expected to teach, and then at the end of the year, their scores would rise, proving I had been successful in teaching them all the skills and material.There is was; proof of my teaching efficiency on nice neat charts. As I recall the charts were supposed to follow the students throughout their high school years, passing from one teacher to another, showing their progress in mastering subjects. Every teacher in every subject area was expected to create these charts for all courses taught.

Eventually, when the State of New Jersey came to the school to assess it, we'd have the charts to prove our worth and just how thorough and efficient we were.

I don't remember all the details of what happened to all those pieces of paper generated by the testing. I can recall cleaning out one of my file cabinets when I retired some thirty years later and finding a folder with charts still in them. I also later moved my classroom to a computer lab that had a nice storage room in back with walls of metal shelves filled with what I discovered to be "monitoring notebooks" dating back to that period of time. These were the reams of paperwork created to satisfy the State Monitors when they came to the school to evaluate and certify our programs.

The books and charts stood as silent testimony to what was to come. It was the beginning of my experience with high stakes testing. Then, I was in charge of the test, but as I was soon to learn, what went on in my classroom was not going to stay in my hands for long.

No comments:

Post a Comment